The Lion's Den Vol. 12 - The Fallacies of the Rule of 40 (Part II)

The Rule of 40 should be applied differently to high- and low-growth companies when assessing whether or not they warrant a premium valuation

In my last post, I discussed the nuances of calculating the Rule of 40 correctly and the implications of pairing the wrong growth and profitability metrics. In this post, I’ll spend more time analyzing the actual output of Rule of 40 and its implication on valuation. The thing is, not all R40 companies are created equal and the two ingredients of this popular KPI, growth rate and profit margin, should have a materially different weight as it relates to how a company is valued. In order to truly compare and benchmark companies, another layer of analysis is required - let’s go!

Fast Growth Trumps Margin. Slow Growth Does Not.

The issue with the Rule of 40 is that it is too generic. The output itself simply doesn’t offer sufficient differentiation between vastly different companies. I imagine most of you will agree that a software company with 0% growth and 40% FCF margin will be valued differently than a company growing 30% and generating 10% margin and much differently than a company with 100% growth and (60%) FCF margin. While these are all technically R40 companies (and let’s assume they’re all the same scale), each of these will likely be relevant to a completely different universe of investors.

A great illustration of how valuation and a simplistic R40 score don’t correlate can be seen in the public market. When analyzing a universe of ~80 software companies (borrowed from Altimeter’s Jamin Ball and his very good Clouded Judgement newsletter), it’s clear that there isn’t a particularly strong correlation between companies’ R40 score and their valuation multiple.

In fact, if you only look at the publicly traded companies that have achieved a Rule of 40 or better you will see that there is no correlation at all between their R40 score and their valuation multiple.

The common denominator for the most highly valued software companies is first and foremost fast growth at scale and, secondarily, sky-high profitability. Within the top 10 highest valued software companies (based on EV/NTM Rev. multiple), every single one grew faster than 20% in the last 12 months. Within the top 20, there are 18 companies that grew 15% or better. The other two? While their growth rates were slightly below 15%, they each generated FCF margin of 35%+ (and had a R40 of ~50%).

So what’s the point? I believe it’s the following:

Companies that are able to grow at least 15-20%/yr at scale (i.e. $150M+ ARR. For smaller companies with $25-150M ARR growth should be at least 25%+) AND achieve Rule of 40 or better are scarce and deserve a meaningful valuation premium. For context, less than ~10% of all publicly traded software companies have achieved that combination

Conversely, companies that grow slower than 15-20%/yr at scale (or slower than 25% for smaller companies), need to hit the Rule of 50 or better to obtain similar valuation multiples

This is not only intuitively true, but also mathematically. Consider the following sample set of 6 similar software companies with varying pairings of growth and profitability that put them right at the R40 mark. For apples-to-apples comparison, let’s assume they all have $50M ARR, identical capital structure, 12.0% WACC and 3.5% perpetual growth rate (yes, I’m aware that assuming a linear growth and fixed margin for all these companies is not realistic, but doing it for all of them makes it comparable). Now let’s run a DCF valuation for each company by discounting their future cash flows over 10 years and in perpetuity back to present value.

The results are quite interesting. The faster growing R40 companies yield a materially higher DCF valuation of $392-418M (or 7.8-8.4x EV/Rev.), while the slow-growing, more profitable R40 companies yield a meaningfully lower valuation range of $237-343M (or 4.7-6.9x EV/Rev.). Almost a 2x delta between the highest and lowest valuation outcomes for different R40 companies.

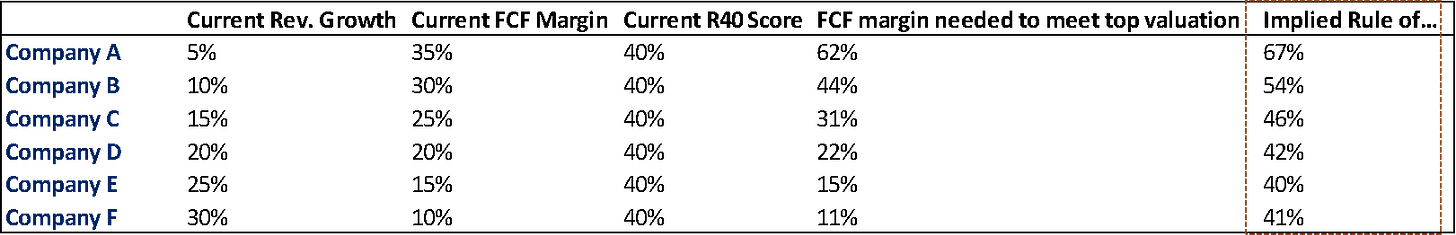

Okay, so both math and intuition demonstrate that the highest quality R40 companies are those that can grow at a fairly high clip AND generate healthy profit margins, but what about those companies whose growth prospects are limited? there are plenty of good companies that will likely experience meaningful diminishing returns from investing for faster growth and simply cannot grow beyond 15-20% without diminishing their Rule of 40 KPI (Dropbox and DocuSign are two examples that comes to mind). For those companies with capped growth prospects, value optimization must come from material margin expansion. To illustrate the point above, let’s go back to our sample of 6 software companies and, assuming their growth rate is capped, let’s see what their FCF margin and corresponding Rule of 40 metric would need to look like in order to generate the same top valuation of $418M based on present value of future cash flows:

The chart above outlines that in order for the slower-growth companies to compensate for limited growth prospects and achieve a premium valuation, they need to showcase Rule of 50 or 60. This conclusion, if you subscribe to it the way I do, should matter a lot to management teams and boards approving budgets and making decisions about the incremental 1% of growth vs. profitability. Often times with slower-growing companies, 1% of incremental growth will “cost” 3-5% of margin and it’s just not worth it.

Final Thoughts

Over the next 12-24 months, I predict a marked divergence in outcomes for private software companies entering the market to fundraise or sell. The top echelon of companies with exceptional growth and efficiency will continue to be highly coveted and garner high multiples, but the real challenge will be for private companies that used to be high growth businesses and are not anymore. Many of these companies are now growing 10-15% and operating in and around the breakeven point at a mediocre scale, which, simply put, is uninteresting for most investors unless it comes at a great discount. To pay a medium-to-high multiple, investors/buyers would need to have a very strong conviction that they could either boost growth or materially expand margins in a way the company hasn’t been able to. This means more private equity control deals at modest valuations (esp. if interest comes down and debt becomes more accessible) and continued drought of large growth rounds. If you’re a series C/D/E/etc. company planning for the next two years, you should take that into consideration.

P.S. - As I was writing this post, I came across two interesting frameworks that I quite like and recommend reading: First is Bessemer’s “Rule of X” and the other is Susquehanna’s “Pathway to the Rule of 50”. The underlying conclusion is similar to mine - high growth is better than low growth, unless a company cannot maintain high growth efficiently, in which case it needs to double down on margin expansion and aspire to be R50 or above.

Onwards!