The Lion's Den Vol. 4 - SaaS Businesses Are Harder to Measure Than You Think (Part II)

Why you should NOT consider LTV/CAC as anything more than a cursory KPI

In my last post about SaaS metrics, I argued that even a simple line item like revenue/ARR can be (and often is) “played with” to mask top line growth issues. Since many of this newsletter’s readers are sophisticated executives and investors, most people agreed. In this post, I expect less consensus. While revenue is a highly debated topic, nothing in “SaaS-land” is more over-romanticized, over-hyped and misunderstood as unit economics. In this post I’ll demonstrate how manipulatable the most popular SaaS KPIs are - CAC, Lifetime, Retention, LTV reporting is extremely variable across businesses and these “degrees of reporting freedom” are further compounded when used in standard calculations such as LTV/CAC. ~5 min. read - Let’s Go!

The Economics of Unit Economics

Measuring unit economic KPIs in SaaS makes a lot of sense conceptually. Software companies usually spend heavily on product development upfront and then on their GTM motion, hoping it will result in long-term contracts or some predictable behavior that will provide visibility into the future and allow better planning, more accurate forecasting, etc. However, these KPIs are only valuable if they can be (1) simple to understand (2) accurate and (3) straightforward to benchmark/compare in an apples-to-apples manner, and those are all real issues today. The reality is that when SaaS companies became more sophisticated and understood the weight investors place on certain unit economic KPIs, the simplicity, accuracy and consistency of these metrics diminished. Even when companies really try, there is just so much wiggle room for major assumptions. Let’s take a look at some of the most commonly used metrics:

Churn / Retention - Understanding what % of customers stay on, pay more or leave is super important and yet retention reporting, even among public companies, is very inconsistent. In fact, when looking at how more than 60 recent IPOs calculated their net revenue retention, there are noticeable nuances in (1) the metric itself (2) definition of churn and (3) the time period used. Take Fastly for example: When Fastly went public in 2019, it reported dollar-based net expansion rate of ~130-147% and repeated that metric 9 times in its prospectus. It requires quite a bit of reading and re-reading to understand that this metric ignores churned customers (i.e. customers that churn are out of the calc., only existing customers that continue paying are calculated) and therefore cannot be compared to any peer’s net rev. retention on an apples-to-apples basis:

“However, our calculation of DBNER (dollar based net expansion rate) indicates only expansion among continuing customers and does not indicate any decrease in revenue attributable to former customers, which may differ from similar metrics of other companies.”

Fastly does report another non-trivial metric called “revenue retention rate”, which sounds like your standard NRR/NDR, right? It isn’t. This metric does accounts for revenue churn, but also for net new revenue. Again, not comparable. Fastly mentioned this metric only once in the prospectus (maybe because it was below 100%…?). You can now probably imagine that if this is the case with public companies, it can be much more complex with private companies that don’t offer the same level of disclosure.

Specifically, when looking at retention, there are a few important nuances to be mindful of:Defining what is a customer is can make a world of difference: Two identical companies could have very different retention rates based on how they define a customer. For example, if a company serves Microsoft in the US and then adds Microsoft Japan as a customer, is that an upsell or a new sale? on one hand, it’s the same logo, same ultimate CEO. On the other hand, this subsidiary might have different procurement departments and decision making processes. Reporting Microsoft Japan as an upsell will boost net revenue retention immediately, whereas reporting it as a new sale will only affect revenue retention when that contract is up for renewal. With that in mind, you can imagine that companies experiencing NRR issues may decide to treat these as an upsell and companies needing to prove they can generate net new revenue may do the opposite.

Serving different types of customers warrants segmented retention reporting. In my portfolio there are companies that serve both enterprise and SMB customers, companies that have industry-specific offerings and companies with a free and paid products. In such instances, looking at a blended retention figure is not only unhelpful, it can be very misleading. In all the boards I am part of, we encourage management teams to break down retention trends in a segmented manner so that real insights about each line of business or type of customer can be gleaned.

Churn calculation should align with contract length. if most of a company’s subscriptions are monthly, annual retention rate is not a helpful KPI. In fact, I find that companies with large base of monthly subscriptions can often have a few large upsells mid-year that can meaningfully move annual retention, but also mask important movements within each monthly cohort that might need to be addressed.

One-off, non-recurring revenues should be excluded from the calculation. Projects, one-off implementations, event-related customers, etc. might spike revenue retention rate in one period and depress it in another while concealing important trends.

Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC) - Few companies go through a highly rigorous process to define what costs should be allocated to CAC. First, because it’s complex to compile and analyze - obvious costs are advertising costs, sales staff, etc. but what do you with rent? admins? software tools? CEOs are always selling to someone - is all their travel CAC? Second, because…there’s no incentive to. Fully loading vs. “kinda” loading CAC will only make the unit economics look less compelling. Most CFOs will probably say (and rightfully so) that the difference is no more than 10-15%, but this CAC delta along with all the other deltas in the LTV calc. can make a BIG difference in the LTV/CAC ratio.

Lifetime & Lifetime value - LTV/CAC is often used to compare and contrast companies’ growth efficiency. I find this metric to be one of the least useful, simply because it’s almost never accurate or comparable. I already mentioned how the denominator (CAC) is often understated, now to the numerator (LTV):

Customer lifetime shouldn’t be guessed - Companies often guesstimate their customer lifetime by simply calculating (1/churn rate). Just because after 4-5 years a company has a 10% annual churn rate, does NOT mean its customers will stick around for 10 years. In fact, that’s a very aggressive assumption. This high level math might be fine for earlier stage companies with little data, but if a company has at least 4-5 years of revenue cohorts…then 4-5 years is their customer lifetime. for now. If it can successfully retain those older cohorts, then it makes sense to gradually increase the customer lifetime or make more aggressive assumptions.

LTV is about gross margin, not revenue - Because not all revenues are created equal (sounds familiar? read my post about revenue “tricks” in case you missed it), to truly understand what a customer value is, it’s important to understand what the cost of delivering that revenue is. Two companies with the exact same revenue, CAC and churn but different gross margins should have different LTV/CAC and potentially different valuation.

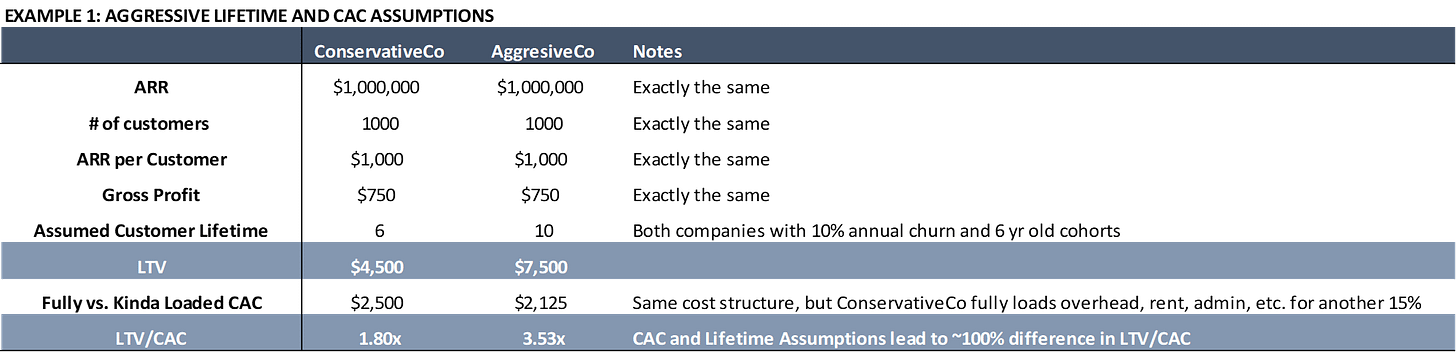

Let’s bring it all together. Below is an illustrative example of two identical companies, one conservative in its KPI presentation and one more aggressive. It exemplifies how seemingly insignificant assumptions around LIFETIME and CAC compound and lead to ~100% difference in LTV/CAC - 1.8x vs. 3.5x for these identical companies.

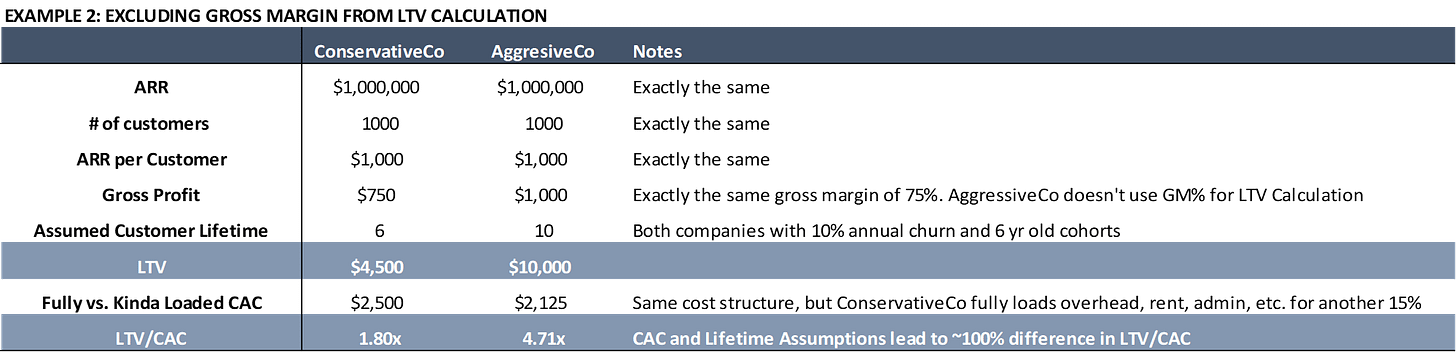

Let’s continue with this example to see the impact of gross margin. Assuming everything stays constant, with the only difference being that in this example AggressiveCo does not include gross margin in its LTV calculation. Now AggresiveCo’s LTV/CAC is 4.7x vs. 1.8x…identical businesses, different reporting.

Now, you tell me - what will the CEO/CFO of ConservativeCo do when they hear that investors got excited by AggressiveCo’s unit economics? Stay true to fundamentals or start flexing numbers?

The reality that everyone has to acknowledge is that investors have romanticized SaaS KPIs and companies quickly learned how to package and present them in a compelling way. Appreciating these nuances and their impact requires pattern recognition and patience, especially in this tricky market where careful diligence and stock picking really matters.

Onwards!

Omer

Follow me on Twitter @omerutah14

Omer, good article. As you say since it is really hard to compare SaaS metrics between companies, I believe it is important to see that an individual company is consistant with its reporting and unit economic trends for that company improve over time.