The Lion's Den Vol. 8 - ESOP, CapEx & The Tooth Fairy

ESOP in software companies is somewhat akin to CapEx in traditional companies - both can have massive, often overlooked impact on cashflows and shareholder value

Warren Buffett is well known for disliking the use of EBITDA for valuing companies, stating this metric can mislead investors. His famous quotes on the topic are well known in the investment community:

“If you look at all companies, and split them into companies that use EBITDA as a metric and those that don’t, I suspect you’ll find a lot more fraud in the former group”

”Does management think the tooth fairy pays for capital expenditures?”

And he makes a good point. Large CapEx investments reduce the cashflows available to shareholders but are not fully reflected in EBITDA, the “standard” cashflow-like metric that is often used to value companies. In fact, in asset-heavy businesses, the gap between EBITDA and real free cash flow can be very meaningful and if you subscribe to the notion that the value of any company is the present value of its future cashflows, using EBITDA may lead to the wrong conclusion.

Software companies, on the other hand, are as asset-light as it gets, but they have a different “cashflow/value diluter” in the form of ESOP. Employee stock compensation in software companies can have a massive impact on shareholder value and, like CapEx, it tends to be overlooked or misunderstood, which leads to a necessary question: “Do companies think the tooth fairy pays for ESOP too?”

ESOP’s Impact on R.E.A.L Cashflow

There is no question that employee compensation is extremely important within the tech sphere. Innovation, execution and speed to market are the name of the game and the only way to continuously achieve those is to hire and retain the best available talent. By offering equity as compensation to employees, software companies align employees’ interest with that of the company, lock in important talent with grants that vest over a period of time, and save cash, the most important KPI in this market.

However, because ESOP is a non-cash expenses that vests over time, its full impact isn’t always obvious when looking into companies’ financial reports. While EBITDA is the "go-to” metric for traditional companies to approximate cashflow generation and for valuation multiples, in software land the prevailing metric is Cash from Operations (CFO) as it accounts for important cash inflows like deferred revenues (cash collected, not yet recognized as revenue). Some investors prefer to look at (CFO-CapEx), but ongoing CapEx for software companies is usually very minimal and doesn’t really move the needle. So theoretically, if you want to evaluate a software company’s ability to generate cash, you could look at the CFO or CFO-CapEx in the cashflow statement. The issue is that CFO also adds back all non-cash expenses including ESOP, which can thwart investors from truly understanding a software company’s true cash generation profile.

Take a look at one of the top SaaS companies, DataDog. in 2021, the company generated $1B of revenue and had CFO of $287M. ~29% cashflow margin is phenomenal, but of that $287M, there was a $164M add-back of non-cash, stock-based compensation…that is a $164M of a real expense that will dilute shareholders. An even more blunt example of this is Snowflake. In its most recent fiscal year, the company generated $1.2B of revenue and had CFO of $110M. However, that $110M CFO included a $605M(!) stock-based comp add-back. Had that expense been a cash expense, it would put Snowflake deep in the red. Interestingly, some of the US-listed European companies (e.g. SEMRush, Criteo) tend to be stingier with their ESOP.

In some of my previous posts I wrote about how SaaS metrics are not always what they seem and ESOP is another example. As the table below shows, the cashflow margin of many software companies would look drastically different if ESOP was considered a cash expense (after all, the company is paying substantial amounts to its employees). No matter how you look at it, the tooth fairy doesn’t pay for ESOP, investors do.

ESOP’s Impact on Shareholder Value

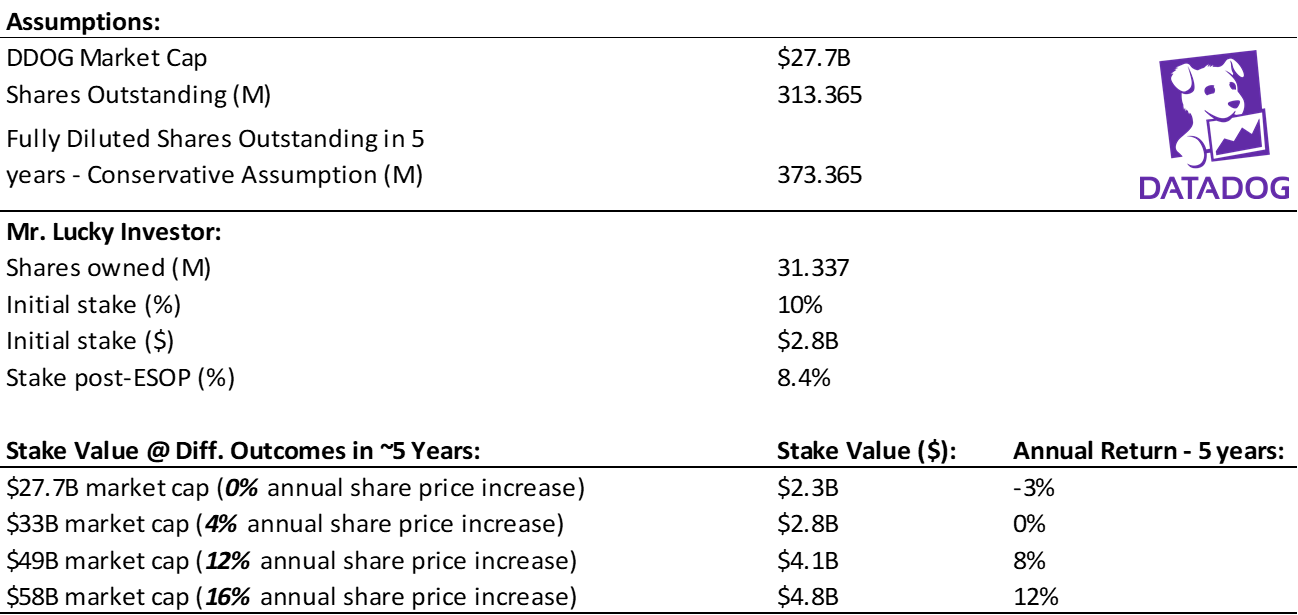

The impact of ESOP becomes most apparent when thinking about valuation outcomes for investors. Shareholders in software companies get continuously diluted over time with the hope that value appreciation compensates for that dilution. How dilutive is ESOP? Let’s go back to DataDog. As of year-end 2021, the company had 313.4M shares outstanding. Let’s assume one lucky investor owns 31.34M shares, i.e. 10% of the company and roughly a ~$2.8B stake. As of year-end 2021, DataDog also had 83.7M options and RSUs outstanding and available for future grant. Even if you assume some employee churn, grants that don’t happen and even if you take into account the minimal proceeds DataDog will receive from exercised options to retire some stock, you’re probably still looking at something like another ~60M shares issued over the next ~5 years.

Now, back to our (un?)lucky investor. If this investor simply holds his position, he/she will gradually get diluted over the next ~5 years from 31.34/313.4 = 10% to 31.34/(313.4+60) = 8.4%. In order to just maintain the $2.8B stake value, DataDog’s stock would need to increase ~19% or ~4%/yr over the next ~5 years. That’s a likely outcome, even in this market, but no investor wants to just maintain their stake’s value (especially in a 8-10% inflationary environment). In order for that investor to generate something close to the historic average S&P return (~12%/yr), DataDog’s stock would need to increase 108% or 16%/yr in 5 years...not that straightforward of a “hold” decision anymore...Once again, the tooth fairy doesn’t pay for ESOP, investors do.

This notion of a dilutive equity pool impacting shareholder value becomes particularly relevant in M&A scenarios. Buyers will run their DCF models and assess total purchase price for the company, which eventually translates to price per share X fully diluted shares. Fully diluted takes into account all the outstanding shares, RSUs, in-the-money options (in many cases even if they’re not vested - M&A serves as the vesting trigger). At any fixed purchase price, the bigger the ESOP pool, the lower the price per share shareholders will receive.

During my time at J.P. Morgan when we advised companies in a sale process, we would run a DCF that assumed all ESOP expenses were cash expenses. This wasn’t 100% accurate, but it showed management and the board what a buyer would consider as the true cashflow generation profile of the company (some buyers may opt to pay more/less cash vs. equity) and how those future cashflows look when discounted to present value.

Final thought: Diving into these types of nuances got me wondering if we are gradually getting to a point where truly understanding technology companies’ financials is beyond the means of an average, and maybe even a somewhat sophisticated, investor. As the complexity of financial reporting rises and the gap between reported numbers and actual performance increases, it’s going to be important for investors to not only understand the business fundamentals, but also truly grasp the financial intricacies of target companies. Interesting times!

Onwards!

Omer

Follow me on twitter